Recently, I had the privilege of attending “Like a rolling marble: Waddington’s landscape vibrant legacy and beyond” a fascinating workshop, held in Lyon, that brought together mathematicians, biologists, physicists, and philosophers of science. The discussions highlighted how Waddington’s epigenetic landscape, conceived almost a century ago, continues to beguile and influence modern biology. I was struck by both the enduring power of Waddington’s metaphor and how it has been co-opted by different generations of scientists in different fields. This workshop took place just a few weeks after I got back from teaching at MBL, Woods Hole, where I was part of the Gene Regulatory Networks for Development course. Comparing those two experiences got me thinking about how, in the era of single cell high-throughput analysis, we can apply Waddington’s insights and Eric Davidson’s work on gene regulatory networks.

Cell fate specification remains a central problem of developmental biology. How is cell diversity produced during development and how is the process organised in space and time? I would argue that two of the most influential frameworks that have shaped our understanding are Conrad Waddington’s epigenetic landscape and Eric Davidson’s gene regulatory networks (GRNs). While these perspectives can be presented as distinct approaches, they share a fundamental characteristic that, in my view, does not receive sufficient attention – they are inherently dynamic.

Waddington’s Landscape: More Than Just Hills and Valleys

Waddington’s epigenetic landscape, proposed in “The Strategy of the Genes” (1957), has proven remarkably versatile as a conceptual framework. The metaphor of a ball rolling down a landscape of hills and valleys has been adapted to explain various biological phenomena, from molecular mechanisms of differentiation to broader evolutionary concepts such as genetic assimilation. It’s ubiquity has meant it has become a cliche with its flexibility being both a strength and a source of misunderstanding.

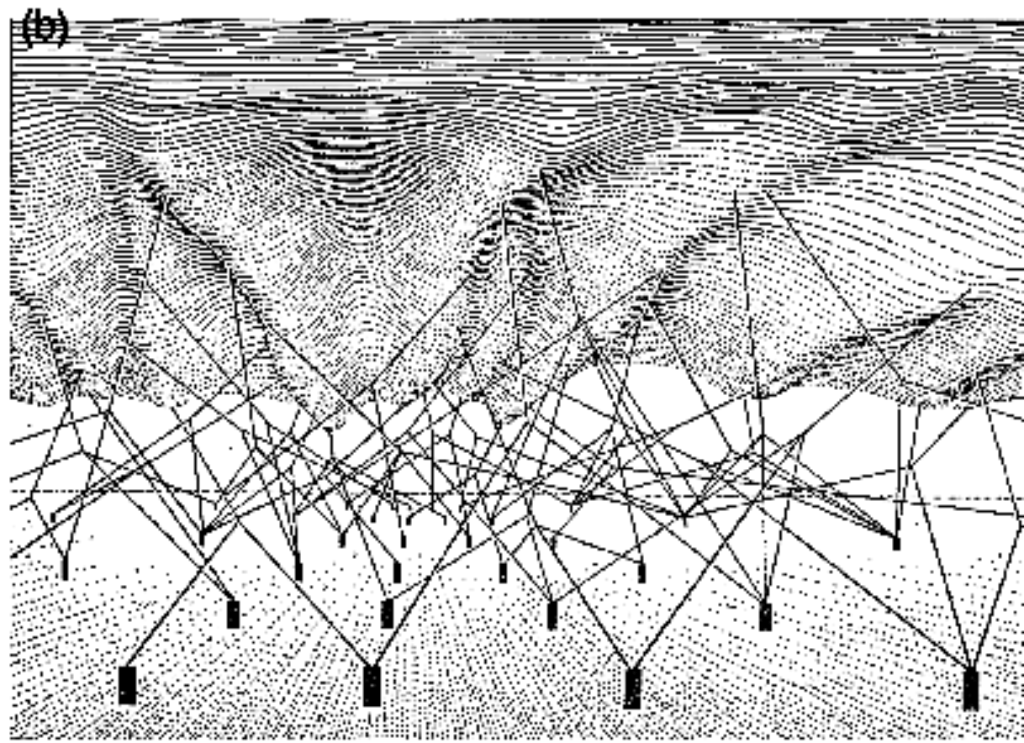

The landscape metaphor has often been reduced to static snapshots – fixed topographical maps of cell fate choices. However, Waddington himself indicated the dynamic nature of his concept. The landscape isn’t a fixed terrain. It is shaped by genetic interactions. Waddington visualised these as a network of guy-ropes pulling the landscape from below, creating and modifying the contours of the landscape. From our 21st Century viewpoint, we can view the molecular and mechanical cues that cells receive as they develop as the inputs adjusting the ropes to modify the landscape.

Waddington’s landscape metaphor found mathematical grounding in dynamical systems and bifurcation theory. Indeed in the 1960s, Waddington corresponded with René Thom, the pioneer of catastrophe theory. This connection revealed deep links between the qualitative behaviour indicated by Waddington’s landscape systems and the geometric approach to dynamical systems. In the language of dynamical systems theory, Waddington’s landscape can be understood as a potential function, the local minima of which represent stable cell states, with the paths between these states corresponding to unstable manifolds connected by bifurcation events. This mathematical interpretation helps explain how continuous changes in cell state can lead to discrete cell fate decisions, and how developmental robustness emerges from the topology of the state space. The mathematical formalisation of Waddington’s ideas through dynamical systems theory provides a rigorous framework for understanding how molecular mechanism generates the landscape’s features and how cells navigate this ever-changing terrain. (For more discussion on dynamical systems and landscapes see <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35860004/>.)

Davidson’s Gene Regulatory Networks: Beyond Static Wiring Diagrams

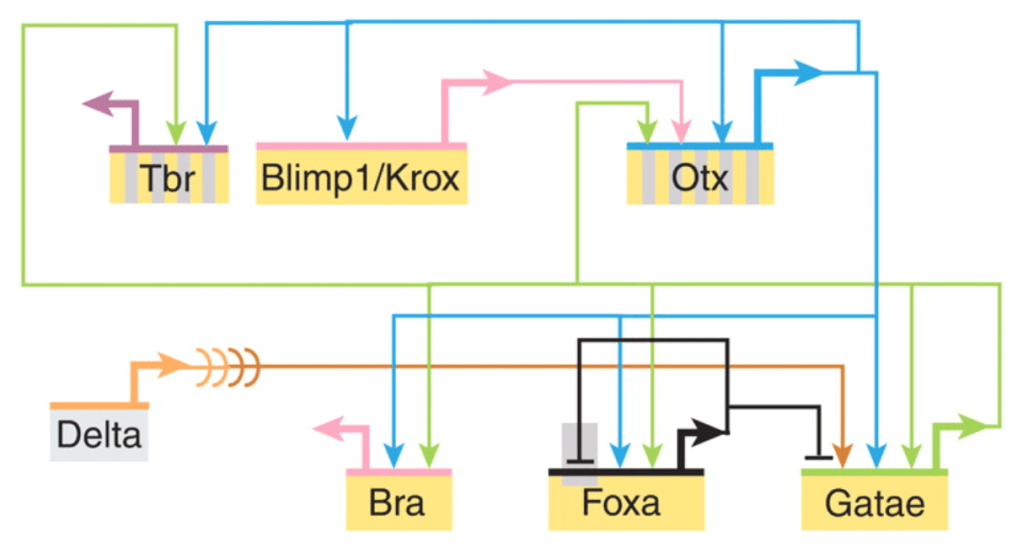

Complementing the Waddington Landscape, Eric Davidson’s work on gene regulatory networks offers a molecular framework for understanding cell fate specification. The GRN theory he developed, inspired by his detailed studies of sea urchin development, revealed the complex hierarchical organisation of transcription factors and signals that drive cell fate decisions. And placed these in an evolutionary context. However, like Waddington’s landscape, GRNs are sometimes misinterpreted as static wiring diagrams.

GRNs are dynamic systems operating in time and space. The networks Davidson described were complex systems with temporal progression, feedback loops, and state-dependent behaviours. Each node in a GRN represents not just a gene, but a dynamic entity the activity of which changes over time, in response to the system’s state. Davidson articulated this through the concept of “regulatory states” – the combination of transcription factors present in a cell at a given time that determines its developmental trajectory. These regulatory states progress through distinct phases during development, with early states setting up the conditions for later ones in a precise temporal sequence. This progression is driven by both positive feedforward circuits that drive cell fate decisions and negative feedback loops that refine and stabilise gene expression patterns. The time delays inherent in transcription, translation, and protein degradation create a system where the timing of regulatory events is just as crucial as their connectivity.

The dynamics of the process are captured within GRN theory by the two complementary perspectives: the “view from the nucleus” and the “view from the genome.” The view from the nucleus considers how the cell interprets its current regulatory state to determine its next actions. At any given moment, the nucleus contains a specific combination of transcription factors that interact with enhancers and promoters to control gene expression. By contrast, the view from the genome considers how regulatory DNA sequences integrate various inputs over time to create specific developmental outcomes. This perspective reveals how the genome encodes not just the components of the network, but also the logic of developmental decisions through the organisation of cis-regulatory elements. These elements serve as information processing units, integrating multiple inputs to produce appropriate outputs in the correct spatial and temporal context. The interplay between these two perspectives – the dynamic state of the nucleus and the hardwired logic of the genome – creates a system that is robust and flexible. It is capable of producing reliable developmental outcomes by responding to external cues.

The Challenge of Single Cell Transcriptomics

The advent of single-cell transcriptomics has revolutionised our ability to study cell fate specification. Results from these experiments have been coerced into interpretations and models that are inspired by Waddington’s and Davidson’s theories. However, single cell transcriptomics predominantly captures static snapshots of cellular states. Although powerful computational methods attempt to infer developmental trajectories from these data, they inherently lack direct evidence of the causal relationships and dynamic processes that both Waddington and Davidson recognised as crucial.

This limitation has led to a somewhat paradoxical situation: we have more data than ever about cell states, yet we are losing sight of the dynamic nature of cell fate specification. Attempts to reconstruct GRNs from single-cell RNA sequencing data often result in static network models that, while useful for generating hypotheses, often fail to capture the temporal and causal aspects essential for understanding development.

To really understand cell fate specification, we need to reconcile the dynamic insights of both Waddington and Davidson with modern experimental approaches. I would argue that we need several complementary advances in both experimental and computational biology. First and foremost, we need new experimental techniques that can capture and test temporal dynamics at single-cell resolution. While current single-cell methods provide unprecedented detail about cellular states, they typically require cell destruction for analysis, making it impossible to track individual cells over time. Technologies such as metabolic labelling, live-cell imaging combined with endogenous reporters, or methods for recording cellular histories in DNA, show promise in filling this gap. (Here’s one of our attempts <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38754365/>.) These approaches could help reconstruct the actual trajectories cells follow, rather than inferring them from population snapshots.

Alongside new experimental methods, we need computational frameworks specifically designed to handle and interpret temporal data in developmental contexts. Current analytical approaches often treat time as just another dimension in a high-dimensional space, but development is fundamentally a directed process with causality and irreversibility, and has arisen from an evolutionary process. New computational methods are needed that account for these features. Incorporating principles from dynamical systems theory or developing new mathematical frameworks that can handle the unique characteristics of developmental processes is required.

The challenge of understanding cellular decision-making also demands the integration of multiple types of data. Single-cell transcriptomics alone, while powerful, cannot reveal the full picture of development. We need to combine transcriptomic data with information about chromatin accessibility, protein levels, metabolic states, and cellular morphology – all while maintaining temporal resolution. This multi-modal approach would help reveal the causal relationships that drive cell fate decisions, moving beyond the correlative insights that dominate current analyses.

Finally, and perhaps most fundamentally, we need to acknowledge and incorporate into analytical methods development’s dynamic nature when interpreting static data. This means being explicit about the limitations of snapshot data and avoiding over-interpretation of apparent trajectories inferred from static samples. It also means developing new ways to validate our interpretations, through perturbation or constructionist approaches that test predicted causal relationships. This shift in mindset – from viewing development as a series of discrete states to understanding it as a continuous, dynamic process – needs to inform both our experimental design and our data interpretation.

The Way Forward

Both Waddington’s landscape and Davidson’s GRNs were conceived as dynamic frameworks for understanding development. As we develop increasingly powerful molecular tools, we must not lose touch with this fundamental insight. The challenge lies not just in generating more data, but in developing approaches that can capture and interpret the dynamic nature of cell fate specification.

The static interpretation of these inherently dynamic concepts has led to an oversimplified view of development. Modern single-cell analysis will benefit from a stronger theoretical foundation rooted in dynamical systems theory. Just as Waddington’s correspondence with Thom helped bridge metaphor and mathematics, we need new theoretical frameworks that connect the vast amounts of single-cell transcriptome data to the underlying dynamics of cell fate decisions. This might involve developing new mathematical tools that infer vector fields and potential landscapes from sparse, high-dimensional data, while accounting for the inherent stochasticity of biological systems. Such theoretical advances, combined with new experimental approaches, could help fulfil the promise of single-cell analysis to reveal the true dynamics of development.